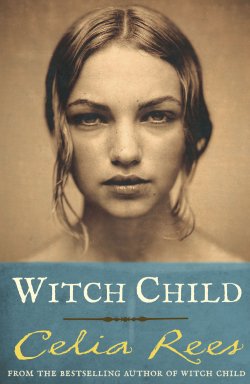

Celia Rees is one of the UK’s most successful and prolific writers of teen fiction. Her work is powerful and wide-ranging, from award-winning historical fiction such as Witch Child to the contemporary realism of This Is Not Forgiveness, taking in pirates, vampires and Shakespeare in other novels along the way.

Here she talks teenage fiction; the roulette wheel of publishing; and what marks out a true writer.

How did you start writing?

‘I started writing in my thirties when I was a secondary school English teacher.

‘I got a sabbatical from teaching to do a Masters degree, and part of it was creative writing. I really enjoyed it and my tutor said my writing was publishable. I got excited about the idea of writing with my students, and when I went back to school, that’s what I did.

‘I wrote more and more, and then somebody told me a true story about a group of teenagers who got mixed up in a murder hunt… so that’s how I started.’

“I hope I write intelligent books for intelligent readers. I expect a lot from my readers. ”

How would you describe your work overall?

‘I wanted to write books for teenagers that were exciting and challenging - like adult books in style, sensibility and complexity – but always with teenagers at the centre of them. When I was teaching I could tell the books my students liked and the ones they didn’t like and I could base my writing on that.

‘I’m fairly uncompromising as a writer. Also, I don’t always write about girls but I do tend to have strong female characters in my books.’

How has the field changed since you started writing?

‘When I first started writing, there weren’t that many people who wrote for teenagers, but the ones who did were very good: American writers like Robert Cormier, Lois Duncan and Patricia Windsor, and in Britain, Alan Garner, Aidan Chambers and Penelope Lively.

‘That was one reason I wanted to do it: because I admired their writing. Any of them could have been highly successful writers for adults - and some of them were – but they chose to write for teenagers. Back then, there were just a few but they were very high quality.’

What’s your writing process or routine like? There’s a huge amount of mystery about how writers actually work.

‘That’s partly because all writers work differently and lots of writers lie!’ she says, laughing.

‘It depends partly on the book. If, for example, I’m writing a historical novel, I will spend about three months at least researching and reading before I start writing anything. I have to do that to see if the story I want to tell is possible within the parameters of the historical period: what was going on, what people did or didn’t do.

“Then I’ll make a plan but it’s not very detailed - a very big spider diagram. I’m seeing really where the story can go and where it’ll take me and if it’ll work. ”

‘And then I’ll write and edit at the same time. I work at it sentence by sentence, paragraph by paragraph, page by page, working through. I revise as I go along.

‘The techniques are different for different kinds of books. With historical fiction I might have to stop and research while I’m writing, so that slows the process down even more.

‘For example, I might be writing away and then I need to find out what sort of red lipstick they were wearing in the 1980s. I might want, say, Chanel Rouge – did they make it in 1989? So I have to go and find that out. It might take a bit of time, but the internet is brilliant for things like that.

‘I write from the beginning to the end. I don’t write episodically. And when I get to the end, I write ‘The End’ and the date and the place. And then I go back to the beginning, doing a first edit, tidying up. Then that’s the first draft.’

And who would you show it to next?

‘Then my first reader will be my husband. He’s a highly experienced literature teacher, an avid reader and very widely read, so he’s a good critic.’

That’s handy!

‘It’s very handy. He’s quite resilient, even though there might be a certain frostiness over the weekend…

‘He will speak his mind but he’s very fair. And if he says it’s good, then it’s good. And if it’s not good he says it’s not good. He’s very honest and he’s very fearless.

‘It always helps to have a break from a piece of work, to put it away or let other people read it. Then I read it again with his comments in mind, and then that’s my second draft. When I’ve done that, that’s the point where I’ll send it off to somebody else to look at.’

What do you think of editing?

‘I never mind re-drafting. Some books of mine need two, three or four drafts. Others will be eight, nine or ten drafts.

“I think that’s the thing that will mark you out as a writer, nothing else. Anyone who finds redrafting boring or tedious is not really a writer. You might be able to write; you might write brilliantly, but if you don’t like redrafting, you’re not a writer. ”

‘Redrafting is never ever boring. It’s the opposite of boring. Hours can go by and you don’t even notice – that’s what marks out a writer from other people.’

Thinking about the YA field more broadly, where do you think it’s going?

‘It’s a difficult question. It seems very fragmented and febrile at the moment. It’s like a big roulette table with publishers constantly moving their chips around from one part to another and never settling on anything.

‘I review for Armadillo, an online children’s book magazine. There are so many books to review! Readers don’t seem to have a chance to settle on anything before another book is thrust under their noses. Writers don’t have a chance to consolidate themselves. It’s a strange picture. It’s not like it’s ever been before.’

Could you pick out a couple of people whose work you admire?

‘I like writers like Melvin Burgess and Marcus Sedgwick. Patrick Ness has been a refreshing new presence. He’s a writer who’s prepared to take risks and push things. I like that. Kevin Brooks is another writer who pushes things. And Sally Gardner: I like what she does.

‘Kate DiCamillo is an American writer who’s won lots of awards in America including the Newbery Medal. She’s a writer of rare wit and intelligence who seems to be able to write everything from picture books to adult and deserves to be even better known here.

‘There are some very good, very experienced writers who are not getting the attention they deserve at the moment, partly because publishers are constantly looking for the Next Big Thing.’

Celia’s writing tips

· Be persistent. You cannot give up.

· You have to be resilient. If people don’t like the work or criticise it or reject it, you’ve got to be prepared to take that. And it’s tough, but you have to do it. It gets easier as you get more experienced.

· Read a lot in your genre. Don’t just read current books. Read the classic books by Alan Garner and Robert Cormier to challenge yourself and see how it could be done.

· Read the very best people in your genre. So if you are writing fantasy, read Philip Pullman and Garth Nix. Read people who are very, very good indeed!

· Be open to ideas. If you have an idea, write it down. Don’t ever reject an idea, no matter how crazy it seems or however it doesn’t fit in with anything else.

· Don’t be afraid of revising. Things can always be improved.

· Write for the sake of it. Write because you want to. Practise, practise, practise. The more you write, the better your writing will be.

Thank you Celia! You can read more on Celia’s website here, find her on Facebook here and on Twitter here.